Nurses’ Homes

Until 1892 the living standards of trainee nurses was varied. RPA had no set nursing accommodation, and nurses could be found sleeping in cubicles off the Front Hall, in terraces on Missenden Road or wherever space could be found on wards and balconies. The first nurses' home, now an education centre, opened with 50 bedrooms in 1892. The number of bedrooms increased to 210 in 1914 and 400 in 1936.

Even this proved inadequate, and in the 1940s, huts were erected at the back of the Hospital. The 11-storey, 750-bedroom, Queen Mary Nurses' Home opened in 1956 – 'so large that it takes one's breath away!'

Living on-site presented many opportunities and challenges. In some ways it was very supportive as one had fellow trainees for encouragement. But in other ways it was restrictive. As one young nurse remarked,

You live with nursing - you can't get away from it. People in other jobs finish work and go home to quite a different atmosphere. Here, you're with nursing 24 hours a day.

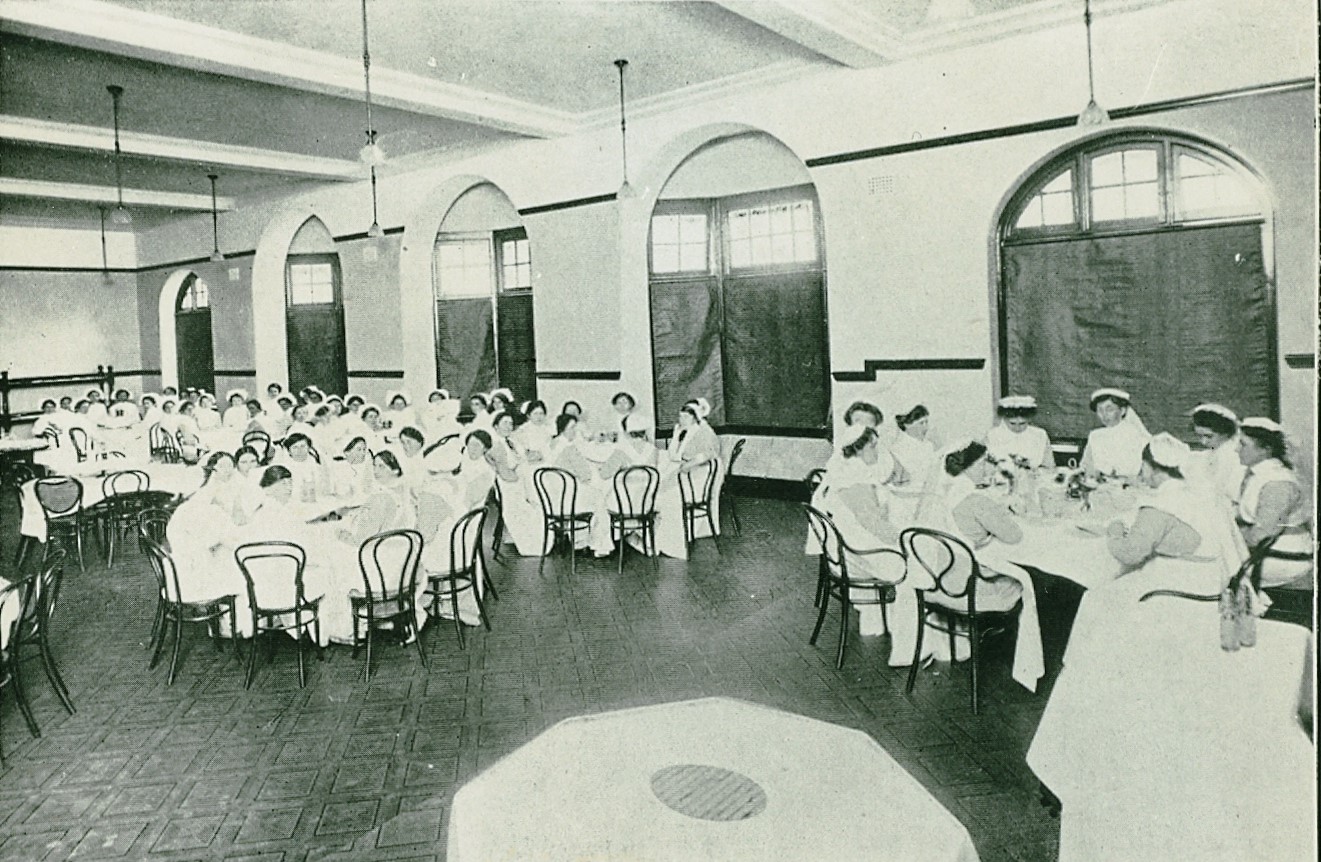

There was strict regulation of meal times, dress and behaviour with very little time off.

A strict hierarchy existed within the nursing staff with the Matron at the top, responsible for all areas of training and with the personal lives of nurses. Seniority applied all over the hospital including in wards, corridors, the dining room and bathrooms. One nurse who trained in the 1940s recalled,

I had no great conflict with Ward Sisters or Staff Nurses. My era/age group expected and accepted discipline in our own homes… we'd had it in our schooling… so that nursing was an extension of this.

Another nurse who trained a decade later saw things quite differently,

'It still amazes me how my vintage of nurses were indoctrinated into instant unquestioning obedience. It became a way of life to say, 'Yes, Sister, No Sister, Three bags full, Sister'... They ruled over their kingdoms with inflexible discipline'.

From 1936 onwards nurse accommodation facilities included showers with hot water, tea making facilities, laundries and irons. Nurses' bedrooms were checked for cleanliness and tidiness, and their Visitor's Room strictly policed. Good camaraderie existed between nurses with small groups congregating to relax in bedrooms. One 1930s nurse trainee remembered,

'…off duty in the Nurses' Home, humiliation was turned into comedy. Authority flaunted. Forbidden cigarettes were smoked, and the unexpected presence of a senior sister in the room sent a hail of burning cigarettes into the wastepaper basket and the nearest nurse pushed on top to cover the offence'.

By the late 1930s nurses had telephone extensions on each floor of the Nurses' Home, as well as radios, parties, yearly dances, plays, revues and musicals in its ballroom. Their lives continued to be strictly controlled, and on days off an exit pass was required to be signed by the Matron with the nurse needing to return by 10pm. Once a month a 1am late pass was given.

One 1930s nurse trainee recalled...

'The Nurses Home, as my father had warned, had replaced the home I had left. One room I occupied opened on to a balcony overlooking tennis courts towards tall jacarandas and flame trees, their beauty a reminder that exams were close'.

During WWII some Preliminary Training School nurses were shocked to discover that during their 1941 training they weren’t to live in the Nurses Home, but in a block of flats in the inner-west Sydney suburb of Summer Hill. One nurse of the time remembered,

…for these weeks we had to travel by train each day in civilian clothes and don our uniforms in a crowded shoe box of a room attached to the school.

A 1940s trainee nurse at the Nurses Home remembered her time fondly,

'...not having been to boarding school, I enjoyed my time with my fellow-trainees, evidently accepting the limitations and rules with few questions. Our own rooms were adequate; I made little effort to decorate. One of our group was an accomplished pianist and it was our privilege and pleasure to come off night duty and to have her play for us briefly before we trooped down to breakfast. The ballroom was a joy, especially in the winter months, the seating comfortable and linen-covered lounges!'

In 1944 Nurses' Huts made of fibro and timber, and uninsulated, were built in St John's College grounds along the drive (later Johns Hopkins Drive). Each had 10-12 cubicles with curtains, but the bedrooms lacked privacy. One nurse recalled,

The only real privacy was the plaster wall between me and my next door neighbour. Every conversation, every snore and every muffled tear filtered through the plaster, through the curtain and over the top of the wardrobe, loudly and clearly.

Another nurse fondly recalled their American male neighbours,

'...these huts were next door to the American Army Military Police barracks and the fraternising was, I honestly believe, completely innocent. The Americans entertained us in groups only. I know we felt very lucky seeing films that had been released in America but not yet in Australia. Often a bar of chocolate would come floating through the window of your cubicle from the other side of the fence (chocolate was very hard to get at that stage of the war)'.

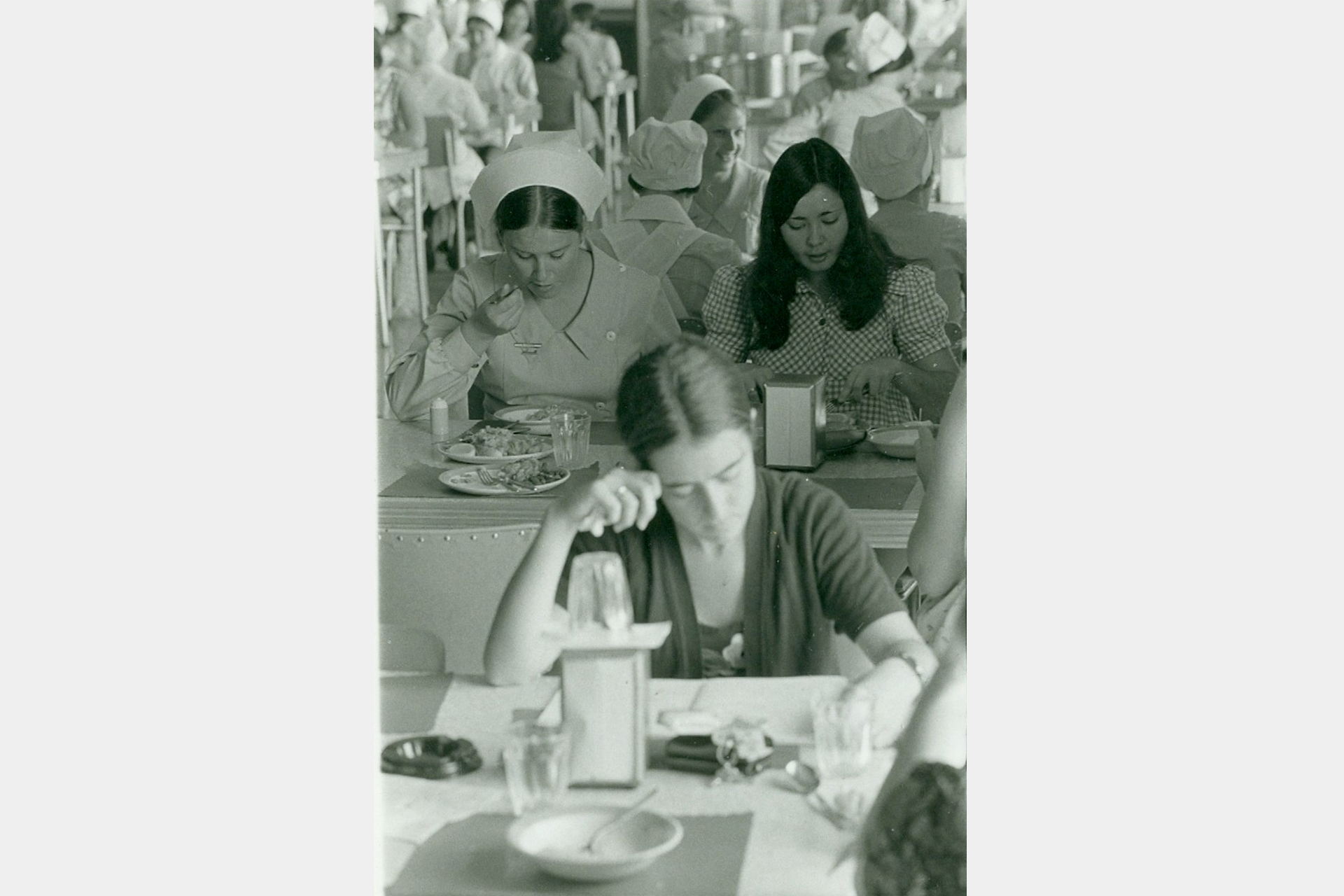

There were complaints and strikes about the quality of food in the 1940s. The food served to nurses at RPA during and after WWII was different to the food served to doctors, sisters and patients. It was considered of inadequate quality and quantity. One nurse remarked,

'...the meals in the beginning weren't so bad, but they deteriorated markedly. The only 'rebellion' that occurred during my four years was because of the food. Many incidents led up to the eruption, but the catalyst was when the kitchen staff refused to keep the meat warm for the second and third sittings of meals. As the second sitting arrived, boiling water was poured over the meat and if any comment was made, you were simply asked if you would like it hot or cold?'

More huts to house and teach trainee nurses were built behind the University of Sydney Veterinary School, near the animal house. Nurses needed to cross the creek on the University Oval and had to remove shoes and stockings in wet weather. Such poor living conditions were the reason many nurses were reluctant to take nurse training at RPA at this time. The huts ceased as nurse accommodation once the new Queen Mary Nurses' Home opened in 1956. They continued to be used as classrooms until the new School of Nursing opened two years later.

Until the 1950s nurses were required to dress in full nursing uniform or in outdoor civilian dress with hat whenever they took meals in the dining room. Nurses were not allowed to eat in the wards. A wooden trolley was wheeled on to the verandah outside the dining room at 10am, 3pm and 8.30pm. It offered trays of bread and jam and large enamel jugs of hot cocoa for nurses.

The Queen Mary Nurses' Home, built for £1.5 million, provided greatly needed accommodation but curtailed freedom of access for nurses. A Home Sister supervised their comings and goings. One nurse of the 1960s described,

'…the corridors lined with small rooms each containing a metal bed, a metal chest of drawers, a metal desk with a metal seat. The built-in wardrobe surprisingly was wood. The room measured five paces long and three paces wide. Short of joining a nunnery it was about the best one intent on doing penance, could come up with'.

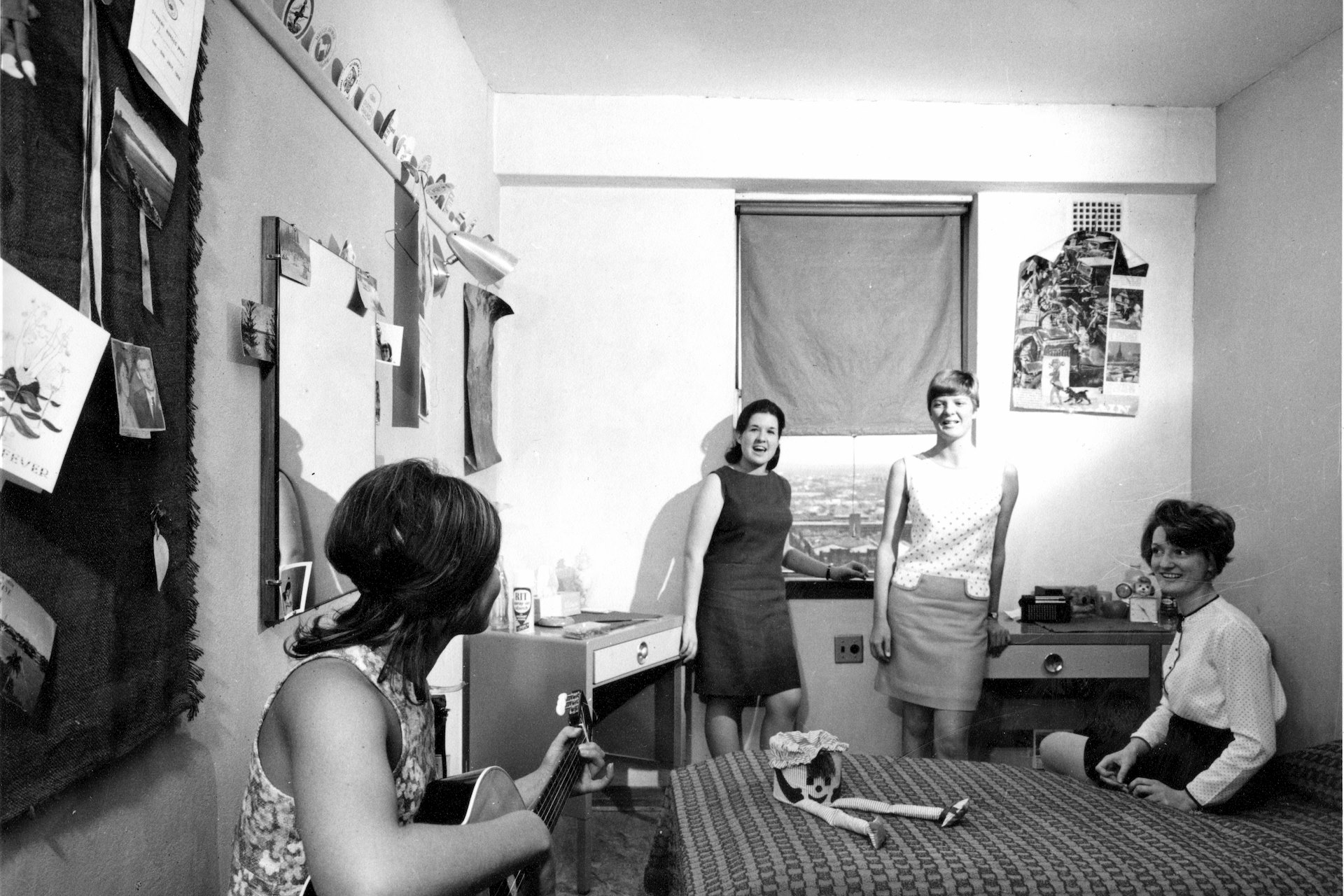

A few years later nurses were allowed, with parental permission, to live out, but only after living in for 12 months. Each room in the Queen Mary Home had a buzzer on the wall, which went off if the nurse had a phone call or needed to get up for a shift. Beds were not to be placed on the buzzer wall, as this may have encouraged girls to 'press snooze.' Girls were allowed to personalise their rooms with their own rug, curtains and bedspread. Birds or fish were allowed as pets. A Sister of the 1960s remembered another pet,

'…once we discovered a nurse here who was keeping a snake under her bed. The snake went'.

Music had to be turned off at 10.30pm. The home had a shop, bank and hairdressing salon. One nurse noted,

'Today there is a lovely modern washing machine and dryer but we had a copper to contend with. Apart from washing clothes, the copper had other uses, for instance, cooking corn cobs and making caramel out of boiling a tin of Condensed Milk!'

Another recalled,

I thought I'd died and gone to heaven when I first tasted the Greek food in the canteen at the Queen Mary Nurses' Home. It was a revelation to a country girl brought up on a meat and three veg dinner.

There were minor grumbles about other issues but on the whole, living together led to a special appreciation for their training years and lifelong friendships.

'The best things were the friends we made, the camaraderie and the fond memories of drinking cappuccino while listening to the guitar and folk music in the coffee shop down Missenden Road'.

Sources: 'The First Fifty Years' by Dorothy Mary Armstrong (1965); 'The Second Fifty Years' by Helen Croll Wilson (2000); The Life and Times of Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia by Muriel Knox Doherty (1996); Australasian Trained Nurses' Journal; The Sydney Morning Herald; RPA Museum collection.